A Guide to Bacon Styles, and How to Make Proper British Rashers

Everyone loves bacon, but it's not always the same thing.

British Bacon vs American bacon

If you've been reading the site lately, you may have been following Nick on his rather strange quest to recreate a full English breakfast from scratch (his first project was the British banger sausage ). Why, I don't know. But when Nick proposed that I take over the homemade bacon portion of the project, I leapt at the opportunity to contribute. Homemade meat curing has long been a hobby of mine, despite the protests of my wife when I hung a pork jowl in our living room. For me, the bacon is the most interesting part on the plate when it comes to proper English breakfast.

The only problem is that the British have got bacon all backwards. They don't traditionally use the familiar bacon cut we know and love in the U.S., and there is a ton of conflicting information out there on the subject.

Vocabulary was my first problem: their bacon is "grilled," which actually means broiled; they refer to pieces of bacon as "rashers," but only if it's a certain type of bacon; the cut that actually looks like American bacon is called "streaky," and whether you choose rashers or streaky says things not only about your tastes, but your economic standing. It's even the subject of a nursery rhyme involving someone named Jack Sprat .

But I managed to make my way through the muck and have emerged with a firm grasp on what seems to be a confounding set of opinions and methods attached to the word "bacon." So I feel a culinary duty to set the record straight, as far as my ability can take me, and in the meantime will be demonstrating how to make yourself a proper hunk of British-style bacon.

The Cut: Making Sense of American, Canadian, and British Bacon

American bacon is invariably made from the belly of the pig, which is not actually its stomach but the fat-streaked padding on the side of the animal. If you've eaten anywhere in the last 5 years you've probably managed to order pork belly as a main course, and if you grew up in America you definitely have eaten pork belly (unless your vegan parents shielded you from one of life's highest pleasures).

Canadian bacon is a product you might see in the U.S. from time to time. It is made not from the belly, but from the loin of the pig, which is the lean medalion of meat you see above. That's why it's a very lean cut, and is reminiscent of slices of ham. It is generally trimmed of fat and, in my opinion, not all that tasty, especially when they coat it with meal made from peas to make peameal bacon . But that's not the subject at hand.

British bacon is a bit like a combination of American and Canadian (though obviously Canadian bacon evolved from the British style and not the other way around). With British bacon, you take the loin but leave lots of lovely fat on it, especially the fat cap, and include the part where the loin attaches to the same cut American-style is made from: the belly. So a full rack of British bacon is the pork loin with plenty of pork belly attached to it: the loin section is the rasher (what [this glossary of British food terms] calls "a thin, floppy slice of fatty ham") and the belly is the streaky. Then you take your pick.

How to Make British-Style Bacon

Though some Brits prefer streaky bacon (Hugh Fearnley-Whittingstall's recipe for Bacon in his Meat book makes no mention of rashers and goes right for the streaky stuff), with a full breakfast rashers are the proper accompaniement. So I set off to find the correct cut and the best method for curing.

The cut, as I mentioned, is basically a loin roast with a bit of the belly attached. Ideally it should have the skin still on, but this is not entirely necessary. Because pigs are butchered differently here than in the UK, my strategy was to find a butcher who sold thick-cut bone-in pork chops and simply ask them to leave me a whole 2-pound piece of the loin they are normally cut from (but with the bone removed). Pork chops with the bone removed but all the fat untrimmed (not the boring pale medallions of meat with no fat) is essentially the cut we're after. Local shop Sterling Goss agreed to cut me a 2-pound piece of meat. Without the fat, you basically end up with a slice of ham; the key with bacon is that it bastes itself and becomes crisp from the present fat melting and rendering.

The curing method is not universal -- my only experience was with American bacon, using a dry cure of salt, sugar, spices, and pink salt. But I came across the phrase " Wiltshire cure " a number of times in my research, which is a "wet-cure" method developed in the 18th century in England to commercially cure bacon. Rather than a dry rub of salt and sugar, it uses a brine and submerges the meat for 3-4 days to cure that way.

I borrowed a brine recipe from the indispensible Charcuterie by Michael Ruhlman and Brian Polcyn. It is as simple as they come, which was how I wanted it. For 1/2 gallon of brine, which nicely covered my piece of meat, I used 1/2 cup kosher salt, 1/2 cup sugar (combination of white and brown), and 3/4 ounce pink curing salt. Other flavorings and spices are certainly welcome at this stage: juniper berries, bay leaves, coriander seed, etc.

The end result is a very simple recipe: hunk of pork, mix brine ingredients, submerge for 3-4 days, and it's ready.

The Cooking

I decided not to attempt to smoke the bacon (about half the bacon in Britian is smoked; the unsmoked product is sometimes called "green" bacon), mostly because I don't own a smoker and my dim memories of eating bacon in the UK didn't conjure up a smoky flavor.

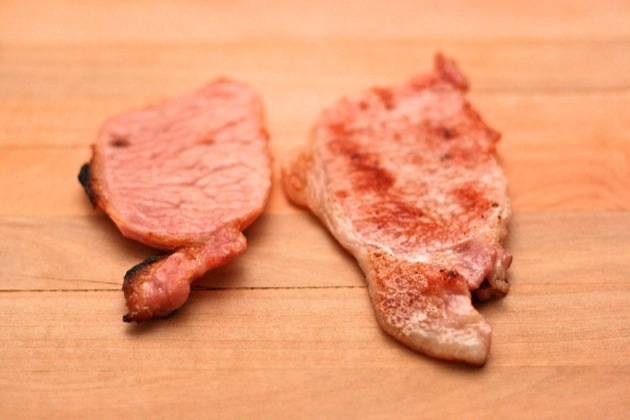

I attempted two cooking methods: "grilling" as they say in England (which I know as "broiling") and crisping up in a cast iron skillet.

Broiled bacon on the left; griddled on the right

The broiled bacon developed a nice char and was certainly pleasant, but I noticed that much of the fat and drippings fell into the roasting pan. Because the loin potion of the rasher is quiet lean, any lost fat is tragic.

Better was the loin cooked slowly in a cast iron skillet. Its fat rendered just enough to lubricate the rest of the rasher, and the whole piece took on a mouthwatering golden outside.

I put it on a plate and ate it with a knife and fork.

Food, Charcuterie, Back bacon, Bacon, Bacon, Breakfast foods, British, Charcuterie, Cuts of pork, Food and drink, Full breakfast, Garde manger, Ham, Homemade Bacon, Jack Sprat, Meat, Nick, Pork, Pork, Pork, Sty, Style Bacon, United States, Breakfast

Comments:

Blog Comments powered by Disqus.